Whip-crack drums peaked in the 1980s. It hasn’t aged well. To be honest, it sounded awful already at the time. There is no clear and agreed definition of "whip-crack drums", but there are some common denominators. First, there should be a big bang - a powerful and distinct drumbeat. Primarly, using the bass (or kick) drum. This was often enhanced with harder drum beaters. In some cases a coin was taped to the beater for a sharper clicking sound. Of course, this was achieved at the expense of the base, tone and warmth of the bass drum. Second, the rack and floor toms were repeatedly and severely battered and beaten. Bang the drum! Third, the use of reverb - an electronically produced echo effect. The ideal soundscape in the 1980s was a snare drum that sounded "big" (as in BIG). In hindsight, not seldom this led to unintentionally comical and vulgar results. The "gated reverb", a powerful reverb that quickly disappeared instead of slowly fade away became very popular. The "gated reverb" was first introduced by Phil Collins (so much to answer for) on "In the Air Tonight" (pay attention to the drum break 3,15 minutes into the song). The impact of "gated reverb" cannot be overstated. It gave the drums a "larger-than-life" sound and is the most obvious marker for drums in the 1980s. To summarize, at all stages; playing, tuning, microphone placement and mixing - a powerful and distinct drumbeat was desired. In my opinion, there are a couple of albums that were damaged more than others by "whip-crack drums"; "Let’s Dance" (David Bowie), "Brothers in Arms" (Dire Straits) and last but not least "Born in the USA" (Bruce Springsteen). British philosopher Alison Stone hit the head of the nail in her book “The Value of Popular Music - An Approach from Post-Kantian Aesthetics”: "Because the snare-drum is smaller than the bass-drum its sounds have higher frequencies (although no precise pitch) and therefore stand out more, so that the snare’s whip-crack sound cuts through the texture more audibly than the duller thud of the bass-drum. The prominence of the snare-drum can be increased further by other means, such as its being struck more forcibly, mixed louder, treated electronically, recorded with echo, or a combination of these. For example, Bruce Springsteen’s ‘Born in the USA’ emphasises the snare drum beats so heavily that they sound like explosions." Could previous big (as in BIG) mistakes be corrected? Yes, all hideous "whip-crack" albums should be recalled and then re-recorded with normal drums. The liberated albums could get a sticker attached to them "This album was recorded without "whip-crack" drums". A lot of albums from the 1980s would benefit greatly from this cleansing procedure. It's not to late.

Whip-crack drums peaked in the 1980s. It hasn’t aged well. To be honest, it sounded awful already at the time. There is no clear and agreed definition of "whip-crack drums", but there are some common denominators. First, there should be a big bang - a powerful and distinct drumbeat. Primarly, using the bass (or kick) drum. This was often enhanced with harder drum beaters. In some cases a coin was taped to the beater for a sharper clicking sound. Of course, this was achieved at the expense of the base, tone and warmth of the bass drum. Second, the rack and floor toms were repeatedly and severely battered and beaten. Bang the drum! Third, the use of reverb - an electronically produced echo effect. The ideal soundscape in the 1980s was a snare drum that sounded "big" (as in BIG). In hindsight, not seldom this led to unintentionally comical and vulgar results. The "gated reverb", a powerful reverb that quickly disappeared instead of slowly fade away became very popular. The "gated reverb" was first introduced by Phil Collins (so much to answer for) on "In the Air Tonight" (pay attention to the drum break 3,15 minutes into the song). The impact of "gated reverb" cannot be overstated. It gave the drums a "larger-than-life" sound and is the most obvious marker for drums in the 1980s. To summarize, at all stages; playing, tuning, microphone placement and mixing - a powerful and distinct drumbeat was desired. In my opinion, there are a couple of albums that were damaged more than others by "whip-crack drums"; "Let’s Dance" (David Bowie), "Brothers in Arms" (Dire Straits) and last but not least "Born in the USA" (Bruce Springsteen). British philosopher Alison Stone hit the head of the nail in her book “The Value of Popular Music - An Approach from Post-Kantian Aesthetics”: "Because the snare-drum is smaller than the bass-drum its sounds have higher frequencies (although no precise pitch) and therefore stand out more, so that the snare’s whip-crack sound cuts through the texture more audibly than the duller thud of the bass-drum. The prominence of the snare-drum can be increased further by other means, such as its being struck more forcibly, mixed louder, treated electronically, recorded with echo, or a combination of these. For example, Bruce Springsteen’s ‘Born in the USA’ emphasises the snare drum beats so heavily that they sound like explosions." Could previous big (as in BIG) mistakes be corrected? Yes, all hideous "whip-crack" albums should be recalled and then re-recorded with normal drums. The liberated albums could get a sticker attached to them "This album was recorded without "whip-crack" drums". A lot of albums from the 1980s would benefit greatly from this cleansing procedure. It's not to late.

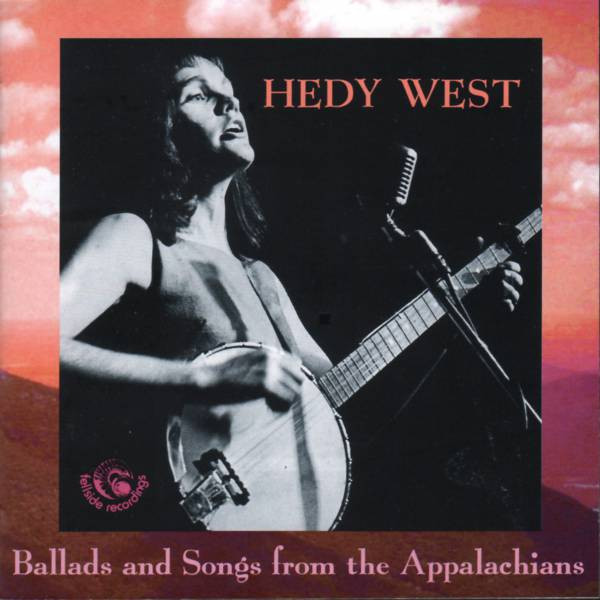

Some albums hit you in solar plexus from the very first note. Why? It's all about authenticity. When you play an original album you hear what the artist intended to put out. Compilation albums seldom have that effect. There is no rule without an exception. I recently stumbled across "Ballads and Songs from the Appalachians" by Hedy West, three classic LPs for the Topic label reissued in a two CD package. The 2-cd was released on british label Fellside Recordings and topped the 2011 Folk Roots critics poll in the reissues of the year category. The album contains no less than 41 songs. It's hard to choose one song over another as everything here is of a very high standard. However, "Fair Rosamund", "Barbara Allen", "The Wife Of Usher's Well", "The House Carpenter", "Pretty Saro", "Little Matty Groves", "The Unquiet Grave", "The Sheffield Apprentice", "Little Sadie" and "The Cruel Mother" stand out. Everything is here; from child ballads, broadsides, religious songs to murder ballads. They depict hard times and unimaginable struggle. Hedy West was born in 1938 in Cartersville, in the poor and rural Georgia, and is regarded as a prominent artist of the 60s folk revival. She died in 2005, but her musical legacy lives on. She had a no-nonsense vocal style combined with stripped-to-the bone banjo playing. Hedy West pass the test of authenticity. Uncontrived, unfeigned and unspoiled to the end.

Some albums hit you in solar plexus from the very first note. Why? It's all about authenticity. When you play an original album you hear what the artist intended to put out. Compilation albums seldom have that effect. There is no rule without an exception. I recently stumbled across "Ballads and Songs from the Appalachians" by Hedy West, three classic LPs for the Topic label reissued in a two CD package. The 2-cd was released on british label Fellside Recordings and topped the 2011 Folk Roots critics poll in the reissues of the year category. The album contains no less than 41 songs. It's hard to choose one song over another as everything here is of a very high standard. However, "Fair Rosamund", "Barbara Allen", "The Wife Of Usher's Well", "The House Carpenter", "Pretty Saro", "Little Matty Groves", "The Unquiet Grave", "The Sheffield Apprentice", "Little Sadie" and "The Cruel Mother" stand out. Everything is here; from child ballads, broadsides, religious songs to murder ballads. They depict hard times and unimaginable struggle. Hedy West was born in 1938 in Cartersville, in the poor and rural Georgia, and is regarded as a prominent artist of the 60s folk revival. She died in 2005, but her musical legacy lives on. She had a no-nonsense vocal style combined with stripped-to-the bone banjo playing. Hedy West pass the test of authenticity. Uncontrived, unfeigned and unspoiled to the end.

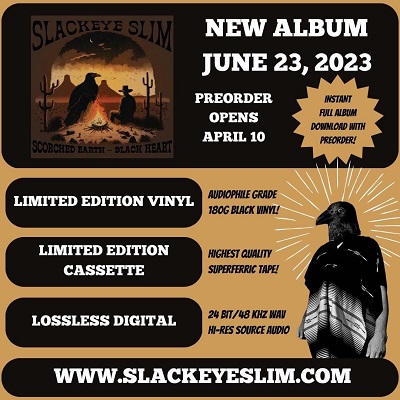

Slackeye Slim is back. Not a day to soon. In fact, it's been over eight years since "Giving My Bones to the Western Lands" was released. The preorder of his new album "Scorched Earth, Black Heart" will open April 10th. Slackeye Slim posted this on his website: "I've been working with Gotta Groove Records on nailing down a solid release date, and we finally got one! June 23, 2023 is the day. By this date I will have the limited edition vinyl and cassettes ready to ship out. Preorders for the limited edition packages will open on April 10, and when you preorder you'll get an instant download of the full album before the official release date! Sorry, no preorder for digital. This offer is only valid while supplies last, and it won't be available for long. We're only making 100 records and 50 cassettes, so don't wait or you might miss out. Preorders will be exclusively available at slackeyeslim.bandcamp.com." No cds at all. I will have to settle with lossless digital (24 BIT/24 KHZ WAV high-resolution source audio). I don't know anything about the album more than it's a concept album written from the perspective of a circular firing squad. This sounds promising. I'm pretty sure it will meet my high expectations.

Slackeye Slim is back. Not a day to soon. In fact, it's been over eight years since "Giving My Bones to the Western Lands" was released. The preorder of his new album "Scorched Earth, Black Heart" will open April 10th. Slackeye Slim posted this on his website: "I've been working with Gotta Groove Records on nailing down a solid release date, and we finally got one! June 23, 2023 is the day. By this date I will have the limited edition vinyl and cassettes ready to ship out. Preorders for the limited edition packages will open on April 10, and when you preorder you'll get an instant download of the full album before the official release date! Sorry, no preorder for digital. This offer is only valid while supplies last, and it won't be available for long. We're only making 100 records and 50 cassettes, so don't wait or you might miss out. Preorders will be exclusively available at slackeyeslim.bandcamp.com." No cds at all. I will have to settle with lossless digital (24 BIT/24 KHZ WAV high-resolution source audio). I don't know anything about the album more than it's a concept album written from the perspective of a circular firing squad. This sounds promising. I'm pretty sure it will meet my high expectations.

The reputable online store CD Baby closed shop without prior notice and without adding any frills: "Where's the CD Baby Store? CD Baby retired our music store in March of 2020 in order to place our focus entirely on the tools and services that are most meaningful to musicians today and tomorrow." Unfortunately, this meant that the tools and services that were most meaningful to me (physical cds) were gone in an instant. I've bought several albums through them; The Broken Prayers: Spanish Wells, The Darklings: Desert Ship, The People vs Hugh Deneal: Gas Station Sandwiches, Woodbox Gang: Drunk As Dragons, Hazy Loper: Ghosts of Barbary, Kal Cahoone: Saints and Stars, Salter Cane: Black Swollen River, Palodine: High Desert Hymns & All the Pretty Wolves, Carrie Nation and the Speakeasy: S/T & Hatchetations, The Maledictions: Idle Hands, Ashcan Orchid: The Woods, Various Artists: Yells From the Crypt, Christian Williams: Defiant, Myssouri: War/Love Blues & FurnaceSongs, Antic Clay: Hilarious Death Blues, The Blackthorns: The Blackthorns, Creech Holler: With Signs Following & The Shovel and The Gun, Pushin Rope: Blood on the Line & Murderous Songs Of Despair and The Roe Family Singers: The Earth and All That is in It. I will miss the long and ironic note in the order confirmations. "Your CDs have been gently taken from our CD Baby shelves with sterilized contamination-free gloves and placed onto a satin pillow. A team of 50 employees inspected your CDs and polished them to make sure they were in the best possible condition before mailing. Our world-renowned packing specialist lit a local artisan candle and a hush fell over the crowd as he put your CDs into the finest gold-lined box that money can buy. We all had a wonderful celebration afterwards and the whole party marched down the street to the post office where the entire town of Portland waved "Bon Voyage!" to your package, on its way to you, in our private CD Baby jet on this day. We hope you had a wonderful time shopping at CD Baby. In commemoration, we have placed your picture on our wall as "Customer of the Year." We're all exhausted but can't wait for you to come back to STORE.CDBABY.COM!! Thank you, thank you, thank you! Sigh... We miss you already. We'll be right here at http://store.cdbaby.com/, patiently awaiting your return. CD Baby The little store with the best new independent music." The order confirmation note was maybe a little bit over the top and the company name CD Baby leave something to be desired. Nevertheless, CD Baby was an important online distributor of independent music. One comparative advantage was the shipping option USPS INTL-AIR NO PLASTIC. Very affordable. On March 31, 2020, CD Baby ceased its retail sale. You will be sorely missed. Thank you, thank you, thank you!

The reputable online store CD Baby closed shop without prior notice and without adding any frills: "Where's the CD Baby Store? CD Baby retired our music store in March of 2020 in order to place our focus entirely on the tools and services that are most meaningful to musicians today and tomorrow." Unfortunately, this meant that the tools and services that were most meaningful to me (physical cds) were gone in an instant. I've bought several albums through them; The Broken Prayers: Spanish Wells, The Darklings: Desert Ship, The People vs Hugh Deneal: Gas Station Sandwiches, Woodbox Gang: Drunk As Dragons, Hazy Loper: Ghosts of Barbary, Kal Cahoone: Saints and Stars, Salter Cane: Black Swollen River, Palodine: High Desert Hymns & All the Pretty Wolves, Carrie Nation and the Speakeasy: S/T & Hatchetations, The Maledictions: Idle Hands, Ashcan Orchid: The Woods, Various Artists: Yells From the Crypt, Christian Williams: Defiant, Myssouri: War/Love Blues & FurnaceSongs, Antic Clay: Hilarious Death Blues, The Blackthorns: The Blackthorns, Creech Holler: With Signs Following & The Shovel and The Gun, Pushin Rope: Blood on the Line & Murderous Songs Of Despair and The Roe Family Singers: The Earth and All That is in It. I will miss the long and ironic note in the order confirmations. "Your CDs have been gently taken from our CD Baby shelves with sterilized contamination-free gloves and placed onto a satin pillow. A team of 50 employees inspected your CDs and polished them to make sure they were in the best possible condition before mailing. Our world-renowned packing specialist lit a local artisan candle and a hush fell over the crowd as he put your CDs into the finest gold-lined box that money can buy. We all had a wonderful celebration afterwards and the whole party marched down the street to the post office where the entire town of Portland waved "Bon Voyage!" to your package, on its way to you, in our private CD Baby jet on this day. We hope you had a wonderful time shopping at CD Baby. In commemoration, we have placed your picture on our wall as "Customer of the Year." We're all exhausted but can't wait for you to come back to STORE.CDBABY.COM!! Thank you, thank you, thank you! Sigh... We miss you already. We'll be right here at http://store.cdbaby.com/, patiently awaiting your return. CD Baby The little store with the best new independent music." The order confirmation note was maybe a little bit over the top and the company name CD Baby leave something to be desired. Nevertheless, CD Baby was an important online distributor of independent music. One comparative advantage was the shipping option USPS INTL-AIR NO PLASTIC. Very affordable. On March 31, 2020, CD Baby ceased its retail sale. You will be sorely missed. Thank you, thank you, thank you!

Seven is heaven, eight is great and nine is fine. I launched the website on March 1, 2014, which is exactly nine years ago, hence "nine is fine". The first blog entry I posted had the dramatic title "So it begins...". Since then I have posted an anniversary blog post every year. The second blog post (2015) had the expectantly title "So it continues...". Here, I discussed the past, present and future for the site. The third blog post (2016) had the prosaic title "And so it goes on and on and on and on and on...". Here, I did some merciless following up on ambitions and promises. The fourth blog post (2017) had the patronizing title "The necessity of content gardening". Here, I stated that a website, with proper content gardening, could live forever. The fifth blog post (2018) had the technical title "Ratchet effect through organic growth”. Here, I speculated how web indexing and algorithms drove traffic to unprecedented levels. The sixth blog post (2019) had the glorifying title "5 years and 100 000 hits". Here, I rattled off statistics lengthwise and crosswise. The seventh blog post (2020) had the dutiful title "The show must go on". Here, I concluded that the responsibilities I have towards society are too important to be calling it quits. The eight blog post (2021) had the explanatory title "7 is the number following 6 and preceding 8". Here, I complained about muddling through in the time of the pandemic. The ninth blog post (2022) had the cheerful title "Eight is great". Here, I made some random remarks. Today, it's time again for a new blog post. The visitor counter indicates 220 038.

Seven is heaven, eight is great and nine is fine. I launched the website on March 1, 2014, which is exactly nine years ago, hence "nine is fine". The first blog entry I posted had the dramatic title "So it begins...". Since then I have posted an anniversary blog post every year. The second blog post (2015) had the expectantly title "So it continues...". Here, I discussed the past, present and future for the site. The third blog post (2016) had the prosaic title "And so it goes on and on and on and on and on...". Here, I did some merciless following up on ambitions and promises. The fourth blog post (2017) had the patronizing title "The necessity of content gardening". Here, I stated that a website, with proper content gardening, could live forever. The fifth blog post (2018) had the technical title "Ratchet effect through organic growth”. Here, I speculated how web indexing and algorithms drove traffic to unprecedented levels. The sixth blog post (2019) had the glorifying title "5 years and 100 000 hits". Here, I rattled off statistics lengthwise and crosswise. The seventh blog post (2020) had the dutiful title "The show must go on". Here, I concluded that the responsibilities I have towards society are too important to be calling it quits. The eight blog post (2021) had the explanatory title "7 is the number following 6 and preceding 8". Here, I complained about muddling through in the time of the pandemic. The ninth blog post (2022) had the cheerful title "Eight is great". Here, I made some random remarks. Today, it's time again for a new blog post. The visitor counter indicates 220 038.

Assessment

Executive summary: The website has operated successfully for the last nine years. New content has been added with regularity and to a sufficient degree without any deterioration in quality. The website is in need of a minor review, primarly with the intent on updating existing pages and removal of dead links. A plan for this has been developed and implemented. Minor disruptancies in the operation of the website have occured, but this haven't affected production or quality. The coming year we will see a strong focus on content and the management and development of the site.

Visitor statistics

To go from zero to 220 000 visitors took 3 277 days. The site didn't have many visits from start. Then the web indexing and Google algorithms began to kick in. The average number of days to reach another 10 000 visitors has normally been around 130-140. The last year has been a record year. More than 37 000 visitors during the last year. All time high.

| Hits | Date | Days | Total |

| 10 000 | 2014-11-20 | 264 | 264 |

| 20 000 | 2015-07-05 | 227 | 491 |

| 30 000 | 2016-03-05 | 244 | 735 |

| 40 000 | 2016-10-21 | 230 | 965 |

| 50 000 | 2017-04-09 | 170 | 1 135 |

| 60 000 | 2017-08-18 | 131 | 1 266 |

| 70 000 | 2018-01-09 | 144 | 1 410 |

| 80 000 | 2018-05-19 | 130 | 1 540 |

| 90 000 | 2018-10-06 | 140 | 1 680 |

| 100 000 | 2019-02-17 | 134 | 1 814 |

| 110 000 | 2019-07-16 | 149 | 1 963 |

| 120 000 | 2020-01-03 | 171 | 2 134 |

| 130 000 | 2020-05-03 | 141 | 2 275 |

| 140 000 | 2020-10-10 | 140 | 2 415 |

| 150 000 | 2021-02-20 | 133 | 2 548 |

| 160 000 | 2021-06-14 | 114 | 2 662 |

| 170 000 | 2021-09-22 | 100 | 2 762 |

| 180 000 | 2022-01-27 | 127 | 2 889 |

| 190 000 | 2022-05-24 | 117 | 2 997 |

| 200 000 | 2022-09-04 | 103 | 3 100 |

| 210 000 | 2022-11-25 | 82 | 3 182 |

| 220 000 | 2023-02-28 | 95 | 3 277 |

I wrote zero new articles last year. New articles have no intrisic value. I don't want to lower my standards. I have a list of 4-5 bands waiting to be included in my prestigious article series. Moreover, I listed 28 new artists in the table, created zero new lists and wrote 34 blog entries (which also is some kind of record).

| Department | 2023-03-01 | 2022-03-01 | 2021-03-01 | 2020-03-01 | 2019-03-01 | 2018-03-01 | 2017-03-01 |

| Articles | 68 | 68 | 67 | 66 | 65 | 62 | 62 |

| Artists | 171 | 143 | 142 | 141 | 138 | 135 | 128 |

| Lists | 42 | 42 | 42 | 42 | 42 | 32 | 27 |

| Blog | 248 | 214 | 184 | 158 | 129 | 99 | 84 |

The five pages below are the most visited. The order has shifted over time. The start page (Home) is and have always been the most visited page. Not very surprising. The second page is the list "10 essential gothic country albums", which comprises a canon of must-have gothic country albums. The third page "Artists" is a simple list with links to Discogs and articles. Review of "Fossils" (Sons of Perdition collaborative album) is placed as number four. The "10 best version of Wayfaring Stranger" list is a newcomer and placed as number five. The Sons of Perdition article page belonged to the five most visited pages for many years. It's now placed as number seven.

| No | Page | 2023-03-01 | 2022-03-01 | 2021-03-01 | 2020-03-01 | 2019-03-01 | 2018-03-01 | 2017-03-01 |

| 1 | Home | 220 038 | 182 591 | 150 601 | 124 031 | 100 813 | 73 857 | 46 277 |

| 2 | 10 essential gothic country albums | 28 662 | 26 981 | 24 663 | 19 722 | 14 372 | 7 540 | 3 946 |

| 3 | Artists | 28 414 | 22 312 | 19 410 | 16 228 | 13 312 | 9 983 | 5 513 |

| 4 | Review of "Fossils" | 19 972 | 16 942 | 13 390 | - | - | - | - |

| 5 | 10 best versions of "Wayfaring Stranger" | 18 632 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

The website has been up and running almost twenty-four seven. Some components have given up. Easy Image Rotator (2022-03-27) and Music Collection (2022-10-09) didn't survive an uppdate and have been replaced. I reached the limit of number of simultanous PHP-processes (2022-06-24), which stopped traffic to the site. I experienced long response times both frontend and backend (2022-08-29). I have done a lot of maintance, but still has some minor things to fix. If you stumble over any obsolete or incorrect information or any dead links don't hesitate to contact me and I will fix it. I take some pride in that the website is updated. On October 23, 2022 the website was succesfully migrated to Joomla 4. At the same time I changed web hosting provider. The site is future-proofed.

Reflections

My junk mail folder is filled to the brim with SEO-obsessed programmers who wants to give advice of how to earn money from the site. The site is non-profit and free of advertisment. This is the way it has been and will always be. One of the strangest suggestions last year was an offer to write blog posts automatically. According to the programmer, it is time-consuming to write a blog post. Another suggestion I got was to use an AI Content Generator since it can be both time-consuming and difficult to come up with content ideas. Yes, but it's fun and rewarding. Other than that, it's business as usual. The Russians try to infiltrate the site and the Chinese try to scam me into buying CN domains. Apparently, China Registry received an application from Hongqing Ltd requested "gothiccountry" as their internet keyword and China (CN) domain names (gothiccountry.cn, gothiccountry.com.cn, gothiccountry.net.cn, gothiccountry.org.cn). There's a reason these e-mails go directly to the junk mail folder.

Future

I will go on untiringly within the limits of family, work and other duties.